- Home

- Nancy Holder

Dead in the Water Page 2

Dead in the Water Read online

Page 2

You pick it up. It’s quite heavy, for something that’s floating. As are you.

There’s a piece of paper inside. A message in a bottle.

And because your hands are shaking, and you’re already getting tired and trying to keep floating; and you’re becoming giddy because you can’t believe this is actually happening—that you’ve drifted out to sea and no one’s come yet—no one’s come yet!—because it makes for something to focus on, a diversion from the fact that you’ve just realized you can’t swim or float or tread water too much longer—

—because you have nothing else to do but be so afraid you want to vomit, you pry off the coating, which is wax, pull out the cork, and tip the bottle upside down.

A piece of thick, yellowed paper slides into your hand. Decorated with an anchor—or is it a skull and crossbones?—the elaborately scrolled letterhead reads:

The Captain, H.M.S. Pandora.

Beneath it are engraved the following words:

The Captain respectfully requests your presence at the Captain’s Table for dinner this evening.

And something rings a bell. Something in the local legends concerning messages in bottles.

And death warrants.

Because no one can swim for very long, and you certainly can’t hold your breath forever.

And when the drowning itself begins? Your actual last few minutes?

You have some final throes, of course. You do not go gentle into that deep ocean. You tire, and so you struggle harder, which tires you more. You tell yourself to float, but you can no longer manage it. You’re hyperventilating. You’re crying. You wet yourself, and the warm stream reminds you how cold you are.

You sink, fight back to the surface, sink, surface, and so on, until you find yourself mindlessly reaching for a gasping, terrified gulp of air. It hurts when you inhale, feels better when you exhale. This seems to go on for an eternity, but ten, perhaps fifteen minutes elapse at most.

Your body is heavy and numb, and clumsy. You can no longer see because you’re blind with fear. You can think of nothing but the next breath.

And you can no longer make your way to the surface. Down, down, you go, and then you struggle against your fate again, but to no purpose. Your eyes bulging, you stare up into the dazzling glare of the sun as it strikes the surface above you; and it looks unbelievably far away, that surface, that sunshine. Conversely, you can see nothing past your feet as they helplessly dangle.

Unbearable pressure pushes against your lungs, so you let the air out a bit at a time—a puff at a time, a slow leak, until your body aches. It feels thin and flaccid, like an empty balloon. Your throat tightens and aches. Your muscles tense and strain.

The surface above you dances and glitters.

Your lungs are almost drained, and you are hovering in the water, and that damn bottle knocks into your head once, twice, and you shut your eyes tight and hope it does the job. But it drifts a few feet away, suspended and unmoving as if it’s waiting—and it is waiting. For your RSVP.

And you oblige. Because you are completely out of air, and now there is only one thing left for you to do.

Inhale.

And just as you do, and your eyes begin to roll back in your head, the shadow of a ship’s hull casts a large, gray net over you and you think, Thank God, thank God, you’re saved.

But you’re wrong. More wrong than you can imagine.

And that is what it will be like. And, more or less, how it will happen.

And it will happen. Sooner. Or later.

So nice you can join us.

I

UNDERTOW

1

Spinning

the Bottle

Glenn Boelhauf slipped his snow-white 1965 Mustang into the parking lot across the street from the Long Beach freight docks. The white sidewalls crunched over gravel, the shatters of a Bud Light bottle, the remains of a dark blue sneaker crusted with dried blood. Across the quay, a long line of semis snaked along, engines rumbling. Air brakes hissed beneath a blast of Willie Nelson on a radio. At the front of the parade, a bright yellow cab airbrushed with a mural of a sunset drove between the towering trestle supports of an immense gantry crane. On his deck, a white boxcar container stenciled “Mazda/Santa Fe 2203022” rode like a fat woman on a parade float.

The crab, a box that slid back and forth across the crane’s bridge several stories in the air, positioned itself over the white boxcar. Rigging whirred down from it like silk webbing from a spider, and men hurried to fasten the hoists to the container.

Glenn let the engine hum for a few more seconds before he turned it off. He caressed the gearshift, gave it a couple suggestive jerks, and grinned at his partner. “New carb’s cherry, wouldn’t you say?”

Donna shook her head and sighed. “You know, for what you’ve blown on this thing in the last six months, you could’ve taken Barb and the kids on the cruise with me.”

He made a face. He was blond, brown, angular; his hobbies were his car and his Top Gun fighter-pilot image, which he’d honed to perfection. Ray-Bans, bronze muscles, straight-arrow khaki authority. Viva Officer Hunk: he and Donna were partners on the San Diego police force. He was senior to her, and the most conceited man she’d ever met.

“Sorry, Donny-O. Hopping rust buckets is not my idea of an alternative to humping my Ford. And anyway, there’s no way on earth I’d take my kids on anything longer than a harbor cruise. You know I can’t stand the little bastards.”

Donna nodded sagely. The only reason he’d driven her up the coast was because he was meeting his wife and kids for a weekend at Disneyland. He’d put in a couple of extra shifts so the little bastards could have all the junk food and souvenirs their greedy hearts desired. Tough guy. Like all the other tough guys on the force. Slammed any show of tenderness, then fell apart when a puppy died en route to the vet’s. Hooted and whistled during the confiscated kiddie porn movies at the keggers and then went home and cried all night because they just couldn’t take it anymore.

“And I sure as hell wouldn’t want to spend my vacation around you,” he added.

Tough guy. She kept her face blank. She’d told him ten months ago the only reason he was having trouble was the way her gunbelt nipped her waist. Tried to be cool, tried to be flip when she laughed off his fumbled confession. That night she put Lady Day, Miss Billie Holiday, on the stereo and sang herself to exhaustion; because they both knew it was her problem, too, and something more than raging hormones; and they both knew it would be deadly to do something about it.

And they both were still working on that. But it was getting worse, not better, and last night, he had been thinking hard about kissing her again; and she knew all about it because she was his partner and she could read his tiny cop pea-brain like a fucking book. Yes, he was conceited, and yes, he was unbearable, and yes, she had been thinking hard about kissing him again, too.

She studied her nails, red and slick, not her usual set of hands. She’d gone to a manicurist yesterday for the first time since she’d become a cop, four years before. Her vacation was a relief, and a reprieve. But it wasn’t a solution. Their mutual attraction would still beckon with its own set of siren fingers when she returned. Donna was going to think a lot while she was out of his sphere of influence. She wondered if he was going to, too, and that frightened her. Because she really did love him, and not just in the girl-boy way. She’d take a bullet for him without hesitation, stand up for him, stand by him no matter what. She loved him like she’d never loved anybody before, a kind of transcendent, spiritual emotion that was subverbal: she couldn’t describe it, she could only feel it. And she sure as hell didn’t want to ruin it just to get her itch scratched.

“Donna, Donna,” he said in a soft tone. She saw herself mirrored in his sunglasses and thought tartly, Not bad for thirty-four, you sultry raven-haired babe. But it wasn’t really very funny. She knew when he looked at her, he saw someone special. Mocking herself didn’t take the edge off that knowledge.

And now he was reading her pea-brain, because he looked away and stared out the window. She joined him. A man in a dark brown jumpsuit had lifted himself up the steps of the truck and was talking animatedly with the driver, who had on a blue baseball cap. It was nine-thirty in the morning; there was a sound in the rhythm of the cranes, the tinniness of the boom-boxes that twanged about a long night of hoisting and loading to get the truckers ready to go back out.

A sea gull wheeled above them, hovered, skittered away. On her side of the car, a flock of pigeons descended on the remains of a cardboard plate of rolled tacos. The freight side of the harbor was very different from the side where the Queen Mary was berthed. Cousin to the Titanic, the venerable old ocean liner had been transformed some years before into a floating hotel. It was popular with honeymooners, anniversary veterans, the romance crowd. When Glenn and Donna swung off the freeway, the sight of it had raised the tension level in the Mustang, particularly when Glenn mentioned offhandedly that he had another two hours before his rendezvous with Barb and the kids. That was the closest they’d come to getting close to it, ever.

Maybe it was being alone in civilian clothes. Together and alone meant work and uniforms. But now there was a hooky-holiday feeling, rules relaxed, like kids ditching school. And yards of bare skin—he had on shorts and a rugby shirt—perfectly pressed, of course, right in style; damn, he was conceited—and she had on a sleeveless sundress that ended midthigh. Miles of skin, and lots of thoughts, and she concentrated hard on the crane and the way it whirred and zizzed, and the two guys jawing, and pondered how much dope came in and out of Long Beach, and who were the dockhands who helped pass it. There was a part of a cop’s brain that never switched off; at least, hers never did. She wondered what Glenn thought about when he made love with Barbara.

Not really.

“Hey, we got you something. I almost forgot.” With a flourish he reached into the back seat and grabbed a dark green champagne bottle banded with a silver bow.

“Oh, baby!” Donna said, holding out her palms. “Come to Mama!”

He snickered, and when she grabbed it from him, she realized it was made of plastic, and too light to have much of anything in it. She held it up to the light through the windshield; it was empty except for something that looked like a wadded piece of cloth. She looked at him quizzically and he snickered again. She hated it when he snickered. It sounded as if his nose was full of goobers. Some of the guys said “bon appetite” whenever he did it. With the American pronunciation. There was this anti-intellectual thing on the force. Nineteen forever, the way the song went. Be cool, hang loose, duh, let’s go beach. No worries about wives and kids and homewrecking, or losing that boy in Tahoe because that idiot Daniel had gotten in her way.

Kiddie-porn movies, just to be contrary. Just to be assholes and to prove they weren’t men and women who bore terrible pressures.

“Open it.” He took off his sunglasses and grinned at her. Big blue aviator eyes. He constantly cracked jokes about modeling for Playgirl.

The plastic cork made a plastic pop as she eased it off. She turned the bottle upside down and shook it. A jot of leopard-pattern fabric and a foil condom package fell into her hand.

He snickered hard. “Read the label.”

“Oh, brother.” She shook the fabric and it unfolded into a jockstrap kind of thing. Holding it like a dead rat between her thumb and forefinger, she turned the bottle with her free hand so she could scan the bright pink sticker on the front. “ ‘Chateau Monsieur Bubble,’ ” she read. “ ‘Spin Me for Lots of Les Kicks and Le Bouf! Fun.’ ”

She laughed and fluttered her lashes. “Jesus, Glenn, just what I always wanted. A leopard-skin jock. Who got this, Martinez?” Carlos was their friend in Vice.

“No way. I bought it myself. And it’s called a sling, cuddle-cakes.” Glenn chortled. “Had to turn down the cashier when he asked me for a date.” He batted her shoulder as she examined the jockstrap doubtfully. “Oh, come on, Donald! It might come in useful. And besides”—he reached into the back seat again—“we got you some of the real stuff, too.”

“What’s Le Bouf! Fun?” she asked, then saw the second bottle cradled in the crook of his arm. Moët & Chandon. Spiffy stuff. “Oh, Glenn, thanks.”

“Oh, hell, the guys chipped in. A little.” He gestured at the sling. “I figure one’ll lead to the other, yes?”

They looked at each other. Yeah, that would solve a few things, if she fell in love with someone else. Maybe. Or maybe it would just make it worse.

She hadn’t told him everything about that scene in Tahoe. He knew about the boy she’d lost, and the interference, but not that she’d been sleeping with the guy she knocked out. With a wobbly grin, she slid two fingers into the socklike pouch and waved at him, hand-puppet style. “Did you buy one of these for yourself?”

“Naw. Tried that one on. It was too small.”

She rolled her eyes. “Why’d I even ask.”

He leaned over then, brushed her lips with his. His eyes widened—he’d obviously surprised himself; he recovered, winked.

“I’d better get rid of you now, Donny-O. I’ve got a date with a mouse.”

“And a duck.” She stuffed the jockstrap and the condom back into the bottle and popped the plastic stopper back in. “Thanks for the goodies, partner. You’re too keen for words.”

“Millions can’t be wrong.” He posed, raising his chin to the light. “Donna,” he said gently. “Donna, I know you’re going to … I …”

She put up a hand to stop him. “Gotta go. Clean exit, okay?”

Clean break.

No. Never.

No. She was not a homewrecker. She would never do anything, anything that would hurt him or the ones he loved.

“I can walk you over there,” he ventured.

“No way, bro. Don’t want you cramping my style.” She jiggled the plastic bottle at him, opened her door, and slung her leg out. “Grab my stuff, won’t you?”

He got out and went around to the trunk. By the time she reached him, he was leaning into it, pretending to struggle with her suitcase. The round of his ass, the way his muscles moved … she stared at him.

With a theatrical groan, he hefted the bag out and set it by her feet. “Christ, what’ve you got in there?”

“Coors,” she retorted. “Somebody told me they don’t sell it in Hawaii. I’m going to make a mint.”

“That’s bullshit. They’ve got everything we’ve got.”

She grinned at him. “That’s for sure, Monsieur Bubble.”

“Hey, fuck you,” he said amiably. Then he grew serious. His hand reached toward her cheek, lowered. “Come back.”

Donna raised her brows. “Well, of course I will, dumbo. Where else would I go?”

Another gull cried. The semis crept forward. The men inside them must be very patient souls. Oh, brave new world. Oh, world …

The boy she’d lost in Tahoe, the one who had drowned. She had run down the trail from the cabin with her bathrobe hanging open, Daniel racing after in the chill air. Slushy snow stung her feet. It was really too late for spring skiing, but serious skiers never believed the season was over until the rocks gouged their boards.

She had run down there, lungs pumping steam, and seen the kid facedown, spinning, oddly, in a circle; very, very slowly, he was a little satellite circling a sun. Donna’s mind raced at fever pitch as she neared the shoreline. C’mon, baby, c’mon, c’mon. Godalmighty, where were his folks?

C’mon, baby. Spinning in a lazy, deadly circle. Something glinted near him, a piece of glass, a toy, maybe. Her mind burst ahead to a door, and her ringing the bell, and telling two strangers their kid was—

No!

She’d pumped hard. Her robe flapped behind her, exposing her naked body. Her cheeks stretched tautly as she hissed through her teeth, damning herself for not running faster. The results of a bad spill the day before seized up her ankle and tried to make her limp. She ignored her pain

. He was a dot on the vast, ice-cold lake. Tahoe never froze; it was too deep. And things that went beneath its surface were said to remain preserved in the frigid freshwater. Another mental flash of a thoroughly upsetting nature, which she forced away.

Then she was dragging him out, half her body submerged in the icy water as she yanked on his wrists and hauled him onto the frosty earth. Hard, cold pebbles cut the soles of her feet. He was practically a baby, with fine brown hair that flared around his head like the fur lining of his hood; yellow reindeer on his red snow mittens. Even shrouded in sopping layers of snow gear, he was vulnerably lightweight.

His lips were blue, his face washed with purple and ivory. Christ.

She leaned over the boy with her ear to his mouth and two fingers on his neck. Thank God, thank the dear Lord, there was a pulse.

Then she slipped on the ice—to this day, she couldn’t figure it—but she tumbled into the water and for a second, just a flash, she thought someone was pulling her—

Then Daniel, the man she’d met in Caesar’s two nights before, flung himself down beside the boy and shouted, “I know CPR!” and smashed down hard on the kid’s chest.

“No, he’s got a pulse.” Donna scrabbled, searching with her feet for purchase. She was freezing; she couldn’t make her legs work. “Don’t do that!”

Daniel rammed down again. A sharp crack split the air: the boy’s ribs. “Stop it, goddamn it! Stop!” she yelled, but he pumped away. “Turn him over! Get the water out!”

The boy started to gag. Daniel brought his hands down on the boy’s chest. The fur on the boy’s hood rippled as he heaved.

“Turn him on his side, goddamn you!”

And then he was vomiting, spewing water and food and bile, and Daniel reared back, startled; and she tried to climb, tried to climb; goddamn it, her ankle just wouldn’t work right; and the boy was spewing it out and she cried, “C’mon, baby! C’mon!”

Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Crimson Peak: The Official Movie Novelization

Crimson Peak: The Official Movie Novelization The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 3

The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 3 The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 1

The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 1 The Book of Fours

The Book of Fours Ghostbusters

Ghostbusters Unseen #2: Door to Alternity

Unseen #2: Door to Alternity On Fire: A Teen Wolf Novel

On Fire: A Teen Wolf Novel City Of

City Of Tales of the Slayer

Tales of the Slayer The Screaming Season

The Screaming Season Beauty & the Beast: Vendetta

Beauty & the Beast: Vendetta Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Carnival of Souls

Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Carnival of Souls Chosen

Chosen UNSEEN: THE BURNING

UNSEEN: THE BURNING Disclosure

Disclosure Not Forgotten

Not Forgotten Beauty & the Beast: Some Gave All

Beauty & the Beast: Some Gave All Possessions

Possessions Pretty Little Devils

Pretty Little Devils The Evil That Men Do

The Evil That Men Do The Angel Chronicles, Volume 3

The Angel Chronicles, Volume 3 Wonder Woman: The Official Movie Novelization

Wonder Woman: The Official Movie Novelization Hot Blooded (Wolf Springs Chronicles #2)

Hot Blooded (Wolf Springs Chronicles #2) Vendetta

Vendetta Carnival of Souls

Carnival of Souls Highlander: The Measure of a Man

Highlander: The Measure of a Man Witch & Curse

Witch & Curse Buffy the Vampire Slayer 3

Buffy the Vampire Slayer 3 Buffy the Vampire Slayer 2

Buffy the Vampire Slayer 2 Vanquished

Vanquished Unleashed

Unleashed The Angel Chronicles, Volume 1

The Angel Chronicles, Volume 1 Saving Grace: Tough Love

Saving Grace: Tough Love On Fire

On Fire Some Gave All

Some Gave All Legacy & Spellbound

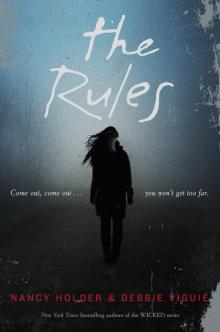

Legacy & Spellbound The Rules

The Rules Resurrection

Resurrection Beauty & the Beast

Beauty & the Beast