- Home

- Nancy Holder

Tales of the Slayer

Tales of the Slayer Read online

“What can I say?” L’Hero laughed. “The people love me, ‘evil demon’ as I am. They know very well that I am a vampire.”

“I protect them and care for them. They know that I have certain . . . limitations, such as moving freely by daylight, and they help us. In return, I treat them well. I give them bread, and a place to sleep. And if they truly merit the honor, I promise them eternal life . . . once we have overthrown the monarchy.”

“Treason!” Edmund cried, as, without a moment’s hesitation, Marie-Christine withdrew a stake and prepared for attack.

L’Hero guffawed. “Slayer, in your journeys through the fair city of Paris, have you not come to realize that the King and Queen are worse vampires than I? That they have sucked the lifeblood of their people, until they are driven mad with hunger and pestilence? The Queen herself has said, ‘Let them eat cake.’

“I say, ‘Let them drink blood.’ ”

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

* * *

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

Contents

A Good Run, Greece, 490 B.C.E.

Greg Rucka

The White Doe, London, 1586

Christie Golden

Die Blutgrafin, Hungary, 1609

Yvonne Navarro

Unholy Madness, France, 1789

Nancy Holder

Mornglom Dreaming, Kentucky, 1886

Doranna Durgin

Silent Screams, Germany, 1923

Mel Odom

And White Splits the Night, Florida, 1956

Yvonne Navarro

About the Authors

A Good Run

Greg Rucka

THE SLAYER THESSILY THESSILONIKKI THE BATTLE OF MARATHON

GREECE, 490 B.C.E.

She runs.

The ground is hard and dry, littered with stones and the bodies of the fallen, Athenian and Persian alike. She runs barefoot and avoids the bodies, but cannot avoid the stones. They bite at her soles, digging into her skin, and she can barely feel it, but she knows her feet are raw and blistered, and that with each stride she leaves a trail of bloody footprints across the plain. She barely feels anything but a distant and crackling pain from her lungs and a dull hot throbbing from the wound in her side, where the poison entered her body almost four days ago. Her chiton, once white, is now almost black in places, stained with days of dirt and sweat and blood, and linen has torn at her shoulder where a vampire grabbed her while trying to take her throat.

That vampire is dead, as are a hundred others, and she is dying, too, but she keeps running.

She has run nearly three hundred miles in four days, and she is almost finished.

In her right hand she carries her labrys. Perspiration from her hand has soaked the leather-wrapped grip, turning it blacker than her filthy tunic, and fine dust clings to the point of sharpened wood opposite the ax head, the part she uses as a stake when a stake is better than a blade. The handle is scored in several places, where she has used it to block blades or blows or teeth, and the head is chipped. The staking end, however, is still sharp. This is her favorite weapon, the one she has used again and again for almost eighteen years.

But now, and for the first time in her life, the labrys is heavy. The poison riding through her veins makes her hallucinate, and when she hallucinates, she loses her grip. Twice already she’s come back to the present from her dreams to find the labrys dropped and retraced her steps to retrieve it. It matters that much to her.

She runs.

Her name is Thessily, sometimes called Thessily of Thessilonikki, though no one she has ever known has ever been as far north as Thessilonikki. It is simply a name, given to the woman who was once a girl who was once a slave and who is now the Slayer.

For a little longer, she thinks. The Slayer a little longer.

She is twenty-nine years old, and ready to die.

* * *

She is twelve years old, and has been a slave all her life.

Her mother is a dream memory who died before she could talk, and Thessily has been raised in the household of Meltinias of Athens, a fabric merchant. She has been well treated, or at least never abused, because only a fool abuses a slave; they’re just too expensive to replace. She has never argued or been difficult, but Meltinias has seen it in her eyes.

Defiance exists in Thessily, and she is biding her time.

Meltinias thinks she is trouble. Smart for a slave, perhaps too smart, and growing dangerously attractive. The girl has hair blacker than the night sky, cold blue eyes that seem to judge everything, and skin that is pale like the skin on the statue of Pallas. Thessily is exotic, and Meltinias has already pocketed several coins by charging other men for the simple pleasure of looking on her. Now that she is getting to be old enough, he is considering other ways he could make more money off of his prized slave.

In truth, he might have done so already were it not for the unblinking stare Thessily so often turns his way. The look is unnerving. He thinks, perhaps, it is a look from Hades. It is a look that will certainly lead to trouble.

But not anymore, because today Meltinias has sold his exotic, Hades-in-her-eyes slave to Thoas, the high priest of the Eleusinian mysteries. Thoas is the hierophant, and if anyone knows how to deal with Hades, it is he. The hierophant, after all, is the one person in all of Greece who can guarantee safe passage into the afterlife.

Meltinias watches them go, the tall, middle-aged priest and the pale-skinned girl. Thoas was almost desperate to purchase the girl, and Meltinias will live well on the sale for months to come. Meltinias breathes a sigh of relief.

And he catches his breath, because Thessily, now outside the door, has turned and looked back at him, and smiled.

And the smile is from Hades, too.

* * *

She is seventeen and Thoas, her Watcher, is at his table in their home, pretending to be at work with his scrolls. It is only an hour before dawn, and Thessily is happy and tired and sore, and when she comes inside, Thoas looks up as if surprised to see her. She knows he isn’t; this is his game, and has been since they started. Every evening she goes out with labrys in hand, to patrol and to slay, and always before dawn she returns, and when she crests the rise above the amphitheater, she can see his silhouette in the doorway of their house, watching for her. Then Thoas ducks back inside, and when she arrives only minutes later, he is always at the table, always pretending that he was not worried.

She loves him for this, because it is how she knows that he loves her.

Thoas looks her over quickly, assuring himself that his Slayer is uninjured. If she were, he would hurry to bind her wounds and ease her pain. But tonight she is not, and so Thoas proceeds as he always does, and asks her the same question he always asks.

“How many?”

“Seven,” she tells him. “Including that one who has been haunting the agora, Pindar.”

“Seven. Good.”

Thessily smiles and sets her labrys by the door, then pours herself a glass of wine from the amphora on the table. “There was something new, a man with orange skin and an eye where his mouth should be.”

“Orange skin or red skin?”

“Orange skin. And silver ha

ir, in a braid.”

“How long was his braid?”

“As long as my arm.”

Thoas nods and scratches new notations on his scroll. “Jur’lurk. They are very dangerous, but always travel alone. You did well.”

Thessily finishes her wine and nods and says, “I am to bed.”

“Rest well, and the gods watch you as you sleep.”

She goes into her room and draws the curtain, then sits on her bed and removes her sandals. Before, in Meltinias’s house, she was simply a slave, and not a very good one. Here, living with Thoas, pretending to be his aide, she is the Slayer.

She is damn good at being the Slayer.

She smiles.

* * *

She frowns.

It is three nights ago, and she is running through olive groves and down hillsides, trying to protect a man Thoas has told her must not die. The Persians, led by their king, Darius, are coming. They will land their ships at the coast in only three days. Athens has no standing army, and the Persians have never been defeated. It is already assumed that the glory of Athens will fall, that the city will be looted, the men murdered, the women raped, the children taken as slaves. The greatest civilization the world has ever known is only seventy-two hours from total annihilation.

But there is a thin hope, and it lives in the man Thessily follows, a man named Phidippides, who is running to the Spartans with a plea for help. It is 140 miles from Athens to Sparta, through some of the roughest terrain Greece can offer, over rugged hills and through cracked and craggy ravines. Phidippides is a herald, a professional messenger, known for his stamina and his speed, and rumored to have the blessing of Pan. He runs with all his heart, trying to pace himself, yet knowing that time is against him, and Thessily admires him for this, if not for the errand itself.

She understands the wisdom of appealing to the Spartans. They are the greatest warriors in Greece, their whole culture is built around war and honor and service and dying. She knows how fierce they can be in battle, because even though the Slayer is forbidden to kill Men, she has battled the Spartans before.

The Spartans are lycanthropes, werewolves, and though they control their bestial nature, Thessily does not trust them. But because they are werewolves, they can save Athens.

Athens knows only that Sparta is great in the arts of war, not the truth behind that fact. That is why Phidippides runs 140 miles to ask for their help.

Thessily runs because with the Persian soldiers there also travel Persian vampires, and the vampires fear the Spartans. Thoas has told her that the vampires will do everything they can to stop Phidippides from reaching his goal.

Thoas is correct.

* * *

The first assault comes only hours into the run, as Thessily parallels Phidippides’s route, staying hidden from the herald’s sight, as the terrain turns mercifully flat for a brief while. She leaps across a small creek, starlight reflected on its flowing surface, trying to stay ahead of the herald, and she sees three of them up ahead, using the edge of an olive grove for cover. The vampires aren’t even bothering to hide their true faces, and without a pause Thessily frees her labrys from where it is strapped to her back, and she flies into them.

She has done this easily a thousand times before, possibly even more than that. Thoas has never found a record of a Slayer who has lived as long as Thessily, who has survived and fought for so many years without falling for the final time. She has been the Slayer for seventeen years now, she has grown up and is growing old, and though her body is not as fast or as strong as it once was, she is still the Slayer, and there are no mortals alive who can challenge her.

She takes the vampires by surprise, and has felled one of them with the labrys before they’ve begun to react. On her follow- through swing, Thessily ducks and spins, bringing the ax up and ideally through another of the vampires, but she is surprised to find she has missed. It is a female, dressed in rags and patches of armor, and the vampire hisses and flips away, and Thessily has enough time to think that perhaps these Persian vampires are a little more dangerous than the ones she is used to when she feels the arrow punch into her side.

It feels like she’s been hit with a stone, and it rattles her insides and pushes her breath out in a rush, and she turns to see the archer, the third vampire, perched in the low branches twenty feet away. Without thinking she drops the labrys and takes the stake tucked on her belt, snapping it side-armed, and the point finds the heart, and the vampire’s scream turns to dust as fast as his body.

Then the other one, the female, falls on her from behind, and Thessily tries to roll with it, to flip her opponent. She feels a tearing of her skin and muscle and the awful pain of something sharp scraping along bone, and she stifles a scream. The vampire has grabbed the arrow sticking in her side, twisting it and laughing. Through sudden tears, Thessily strikes the vampire in the throat with the knuckles of a fist, forcing the once-a-woman back, and it buys her time.

Thessily is out of stakes. Her labrys is out of reach. With one hand, she holds the arrow against her body. With her other, she snaps the shaft in two, turning the wood in her hand even as the vampire leaps at her throat again. Thessily drops onto her back, bringing the splinter up and letting the vampire’s own motion drive the stake home. There is an explosion of dust and the all-too-familiar odor of an old grave, and then the night is quiet again.

Thessily lies on her back, catching her breath. After a second she hears the sound of Phidippides’s sandals hitting the soil in a steady rhythm, the shift of the noise as he comes closer, then passes the grove, then continues on his run. There is no pause or break in his stride, and she believes he has noticed nothing, that she is still his secret guardian, and she is grateful.

She tries to sit up and the pain blossoms across her chest, moving around and through it, and she gasps in surprise. In all the years she has been wounded, she’s never felt a pain like this. She looks down at the remaining shaft of arrow jutting from her chiton, the spreading oval of blood running down her side, and gritting her teeth, she yanks the arrowhead free. Her head swims, and she sees spots as bright as sunlight. She raises the arrowhead and tries to examine it in the starlight, sees only the metal glistening with her own blood. She sniffs at the tip, and recoils, dropping it.

The odor burns her nostrils as she gets to her feet and retrieves her labrys. The straps on one of her sandals have torn, and she discards the other rather than try to run in only one shoe. She turns and follows after Phidippides, and has only gone three strides when she feels the first distant wash of nausea and giddiness stirring.

And she knows that she has been poisoned.

* * *

It is hours later that same night, and she has fought eight more vampires, each time keeping them from Phidippides. The vampires are savage and fast, and she is already tired and hurt, and slowing.

She wins each fight.

She runs.

* * *

It is today, and now she runs with Phidippides following, not caring if he spots her, because it is finished and because she is going home. Behind her lie the remains of the battle, where Athens met its enemy that morning. Six thousand, four hundred dead Persian soldiers litter the field, lying together with the bodies of one hundred and ninety-two Athenian men who have given their life for their city.

The sunlight is fierce above, and Thessily trips as she comes off the plain called Marathon. She tumbles through dirt and scrub before she can find her feet once more. She has lost the labrys, and loses precious seconds of her life trying to find it again.

Athens is only ten miles away, now, she can see it in the distance to the south, shimmering with color. Sunlight glints gold off the statue of Pallas Athena, off the tip of the mighty goddesses’ spear.

She continues to run. Thoas is there, waiting, and she has to tell him that they won.

She has to tell him that she is ready to die.

* * *

She is nineteen, and full of herself, an

d is fighting a mob of vampires called the Horde, who have taken up residence at Delphi. She attacks with flaming oil and her bone bow, then with her labrys, then with her stakes, and she kills dozens, and still there are more, because they are, after all, a horde.

One gets behind her and puts her in a headlock, yanking her off her feet, and she can feel his breath burning her neck. His breath smells like rotten meat. Another is charging at her from the front, either not caring that she is already pinned, or hoping to capitalize on the moment, and he has a sword in his hand.

Thessily tries to go up, to flip herself out of the headlock and out of the way, so that the one vampire will stab the other. But as she tries to move, she feels the fangs tear at her neck and then the sword punching through her side, and it is the sword that saves her, because after it goes through her, it goes into the vamnire behind her, and his teeth leave before he can take her blood.

She screams with rage, and as the vampire with the sword pulls it free, she reaches blindly for his head and snaps his neck, taking the sword from his hands as he dies. She spins with the blade and takes the head of the one who had bitten her, shouting hatred at him as he dissolves.

Thessily staggers out of the caverns beneath the temple, one hand across her belly, trying to keep her insides inside. Dawn is breaking, and she hears the sea and smells the salt, and then the sound of the waves grows louder and louder, and instead of the world growing lighter it grows darker, and she collapses on the road.

She nearly dies. She survives only because someone brings her to the Oracle, and the Oracle knows of the Slayer. The Oracle sends for Thoas and tends to Thessily, and for three days Thessily is unconscious, until finally she awakens, and her Watcher is there, and he looks concerned.

“I’m fine,” Thessily says.

Thoas shakes his head.

“Truly, Thoas, I’m fine.”

Thoas rubs the crow’s feet at his left eye, the way he does when he is trying to find the right words. Thessily smells the camphor and lime on the bandages around her middle, and fights the urge to scratch the wound. In three days it will be healed, and there will not even be a scar. She hears voices singing praises through halls far away.

Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Crimson Peak: The Official Movie Novelization

Crimson Peak: The Official Movie Novelization The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 3

The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 3 The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 1

The Angel Chronicles, Vol. 1 The Book of Fours

The Book of Fours Ghostbusters

Ghostbusters Unseen #2: Door to Alternity

Unseen #2: Door to Alternity On Fire: A Teen Wolf Novel

On Fire: A Teen Wolf Novel City Of

City Of Tales of the Slayer

Tales of the Slayer The Screaming Season

The Screaming Season Beauty & the Beast: Vendetta

Beauty & the Beast: Vendetta Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Carnival of Souls

Buffy the Vampire Slayer: Carnival of Souls Chosen

Chosen UNSEEN: THE BURNING

UNSEEN: THE BURNING Disclosure

Disclosure Not Forgotten

Not Forgotten Beauty & the Beast: Some Gave All

Beauty & the Beast: Some Gave All Possessions

Possessions Pretty Little Devils

Pretty Little Devils The Evil That Men Do

The Evil That Men Do The Angel Chronicles, Volume 3

The Angel Chronicles, Volume 3 Wonder Woman: The Official Movie Novelization

Wonder Woman: The Official Movie Novelization Hot Blooded (Wolf Springs Chronicles #2)

Hot Blooded (Wolf Springs Chronicles #2) Vendetta

Vendetta Carnival of Souls

Carnival of Souls Highlander: The Measure of a Man

Highlander: The Measure of a Man Witch & Curse

Witch & Curse Buffy the Vampire Slayer 3

Buffy the Vampire Slayer 3 Buffy the Vampire Slayer 2

Buffy the Vampire Slayer 2 Vanquished

Vanquished Unleashed

Unleashed The Angel Chronicles, Volume 1

The Angel Chronicles, Volume 1 Saving Grace: Tough Love

Saving Grace: Tough Love On Fire

On Fire Some Gave All

Some Gave All Legacy & Spellbound

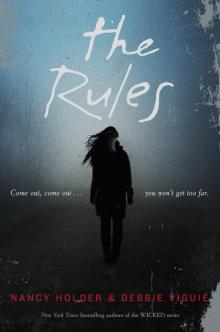

Legacy & Spellbound The Rules

The Rules Resurrection

Resurrection Beauty & the Beast

Beauty & the Beast